When it came time for my dad to get married, my dad’s ideas and his family’s ideas differed significantly and this is where the biggest obstacle of all came to the forefront. My dad’s struggles in America came about years after he immigrated and were not a result of external factors, but rather, internal family and cultural pressures. My dad had fallen for an American woman, my mom, and this was a problem. A line from the movie My Big Fat Greek Wedding explains the Greek tradition well, “The only other people we know are Greeks, ’cause Greeks marry Greeks to breed more Greeks.” Most other Greeks my family knew, were married to other Greeks. In fact, my dad’s own parents’ marriage was arranged.

So, my dad’s decision to marry Mary Featherston, a Roman Catholic woman with Irish, Portuguese, and English roots, caused quite the stir. This meant he would not have fully Greek children, he may not baptize his children in the Greek orthodox church, and he may not follow the Greek tradition which requires sons to welcome their mothers into their homes to care for them when they get older.

My dad’s decision to marry my mom caused him to be essentially “disowned,” as he puts it. His family was not at the wedding, nor were any Greeks, as a result of my Yia-Yia advising them not to attend. My dad’s decision to marry an American makes him different from most Greeks he knows. Most Greek’s he knows married other Greeks. However he jokes, “All of my Greek friends except for one married Greeks, and today they are all divorced.” My dad’s goals were to get married, have kids, and own his own business. Marrying a Greek simply because she was Greek, was not a priority.

There are some variations among Greeks in regard to how much of their Greek culture they hang on to and how much they let go of, a lot of which has to do with marriage. If my dad followed my Yia-Yia’s orders and married a Greek woman, perhaps he would have held on to more Greek traditions.

While my dad’s decision to marry a non-Greek caused problems within his family, today this is a decision that more and more Greeks have been making. Looking at the history of Greek marriages helps explain why there was such a strong expectation for my dad to marry a Greek woman. In 1926 just one in five Greeks in America entered into mixed-marriages, marriages in which Greeks marries non-Greeks (Moskos 2014). Thus, my Yia-Yia who grew up in Greece, not only expected that my dad would marry a Greek because that was just what Greeks in Greece did, but also because statistics show that even in America, most Greeks were marrying Greeks. By the 1960s, though, this number began to dwindle and only about seventy percent of Greeks were marrying other Greeks in America. Today, this number has shrunk even more, as seventy-five to eighty percent of Greeks have non-Greek spouses (Moskos 2014). So my parents’ marriage which took place in 1990, occurred during a time when intermarriage rates among Greeks were on the rise. However, my Yia-Yia’s discontentment may have stemmed from the fact that she grew up in Greece and so did my dad in the early years of his life. Because of this she felt a strong connection to the traditions of Greek culture that other Greek Americans who did not grow up in Greece may not feel, making their decisions to marry outside the ethnic group less controversial. My Yia-Yia, however, is definitely not the only Greek mother to be unhappy with the decision of her child to marry a non-Greek. Moskos (2014) writes that “…the initial edict of the immigration parents was to tell their children that all Greek spouses were better than all non-Greek” (Moskos 2014: 150). Mosques says, however, that today it is practically “unheard of” today for Greek parents to “break social relations with the errant child and then relent once grandchildren arrived,” but this is exactly what happened in my family’s situation. Moskos says this typically does not happen anymore because more acceptance for inter-marriages has arisen solely out of the prevalence of them, but unfortunately the increase in prevalence did not keep my Yia-Yia from expressing her disappointment.

While at the time my dad was seen as different from other Greeks because of his decision to outside of the ethnic group, he remained similar to many Greek immigrants in the way he fulfilled one of his three goals that I previously mentioned, owning his own business.

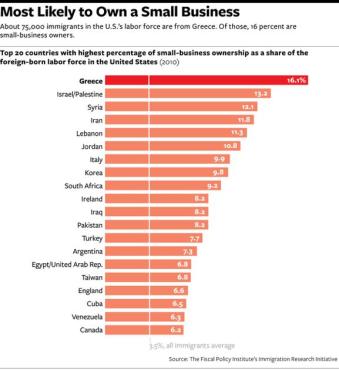

Immigrants from Greece make up a small percentage of all immigrants in the labor force. However, sixteen percent of all Greek immigrants in the American labor force are small business owners. This is the highest share of any group of immigrants (Fiscal Policy Report 2012).

Immigrants from Greece make up a small percentage of all immigrants in the labor force. However, sixteen percent of all Greek immigrants in the American labor force are small business owners. This is the highest share of any group of immigrants (Fiscal Policy Report 2012).

In 1985 my dad bought his first business, a small grille, “KC’s Grille.” In 1987 he moved literally right next store to a deli, “Cove Variety.” My parents owned and operated Cove Variety throughout their engagement and early years of their marriage. In 1994, my dad sold the deli and upgraded to a a small, neighborhood grocery store, “The Market Basket,” located just down the street. A year later, in 1995, he purchased another business two doors down which he named “The Wine Basket.”

The Market Basket was my dad’s pride, joy, and sometimes headache for over twenty years. It was all my siblings and I’s first job. It was where my dad taught us the value of hard work. When my Yia-Yia was alive she too helped out, helping my dad make his “famous” chicken cutlets behind the counter every so often. But after twenty-one years of seventy plus hour work weeks, my dad bittersweetly decided it was time for a retirement-from the food business, at least. This past summer, my dad sold the Market Basket and retired to just the Wine Basket.

Despite our only half-Greek status, my Yia-Yia loved my siblings and I dearly. When my parents’ first child, my older brother, Paul Jr. (PJ), was born, my Yia-Yia made some amends with my parents for the sake of being part of the lives of her grandchildren. Spending much of my toddler years with her, I came to know and speak Greek very well, though I regrettfully know only a few words today.

Though our parents raised us Catholic, we maintained some Greek traditions with my Yia-Yia. We would celebrate our Easter and also Greek Easter, we would follow the tradition of eating cheese pie on New Years Day. We would sometimes go to the Greek church, where she loved showing us off. To her and her friends we were not PJ, Katie, Michael, Peter, and Carolyn. We were Apostole, Katarina, Panagioti, Michalis, and because Carolyn does not translate, she was “Kouklitza,” meaning “little doll.”

My Yia-Yia’s funeral in 2006 was one of the last times my family and I went together to mass at the Greek Orthodox church. I maintain some Greek traditions like baking Greek desserts every so often that I know we all love. Each summer the Greek church has a festival. We will sometimes go, pick up some Greek food, and light candles in the church. But these little actions are pretty much the extent of the way Greek culture shines through in the life of my family today.

The concept Mary Waters refers to as symbolic ethnicity accurately explains the way my siblings and I embrace our Greek culture as second generation Americans. Symbolic ethnicity is described as the “American need to be from somewhere” (Waters 1998:150). Waters explains that having an “ethnic identity is something that makes you feel special and simultaneously part of a community” (Waters 1998: 150).

We like that we are Greek and enjoy doing “Greek” things periodically, but we really do not know much about Greek history or the struggles involved with growing up in Greece that my grandparents and dad endured. We are essentially Greek when we want to be.

The generational assimilation of my Yia-Yia, then my dad, then my siblings and I, can be seen more as a straight-line assimilation. It has been a natural progression where we have become more Americanized over time. While this theory of assimilation fails to capture the experiences of many groups, it accurately captures what my family has experienced. Having family already here helped my dad and his parents ease into American life, while holding onto many of their Greek traditions. My Yia-Yia always maintained her Greek culture, going to the Greek church, expecting my dad to marry a Greek, wearing black when my Papau died, and more. My dad distanced himself a bit from the culture as he got older, and eventually started going to the Catholic church instead with my mom. Today as I mentioned my siblings and I acknowledge our Greek heritage but are completely Americanized in a way that my Yia-Yia was not. Thus, over generations, my family has shed most Greek traditions and adopted more American ones.

Despite this though, my dad is proud of where he is from and proud that we are Greek. He has always joked that the five of his kids are fifty-one percent Greek, and forty-nine percent everything else. My dad talks about his identity saying, “Greece is the country I was born and Greece is the country I love from the bottom of my heart but I chose to be an American citizen, and I would fight for this country to my death.” He goes on to say, “…I would die for this country because of what it is has given my family and myself.”